Nation and Government

When a nation goes down, or a society perishes, one condition may always be found; they forgot where they came from. They lost sight of what had brought them along.

—Carl Sandburg (1957)

We can also use a class approach to understanding state institutions by determining which forms of social transfer push governments away from serving their constituents by improving social equity.

Optimising competitive markets

The single most important economic function of modern governments is to limit the extreme inequity of unconstrained capitalism. Unfortunately, this critical role of regulation—limiting market transfers like pollution and monopoly profits, ensuring banks invest client savings safely, investment funds have real assets to cover default risk—is easily characterised as inefficient in good times, and only briefly exposed to public debate after crises.

“Crisis Economics” Nouriel Roubini:

In order to stabilize the system even further, all banks—including investment banks—should be forbidden to practice any kind of risky proprietary trading. Nor should they be permitted to act like hedge funds and private equity firms. Instead, they should confine themselves to doing what they’ve done historically: raising capital and underwriting offerings of securities (p232).

Regulators need not fear that cracking down on these instruments (derivatives) will somehow imperil economic growth. Far from it: their continued existence poses a far greater danger to global economic stability (p203).

The wall of liquidity and the Fed’s suppression of (bond market) volatility can keep the game going a bit longer. But that means the asset bubble will only get bigger and bigger, setting the stage for a serious meltdown (p291).

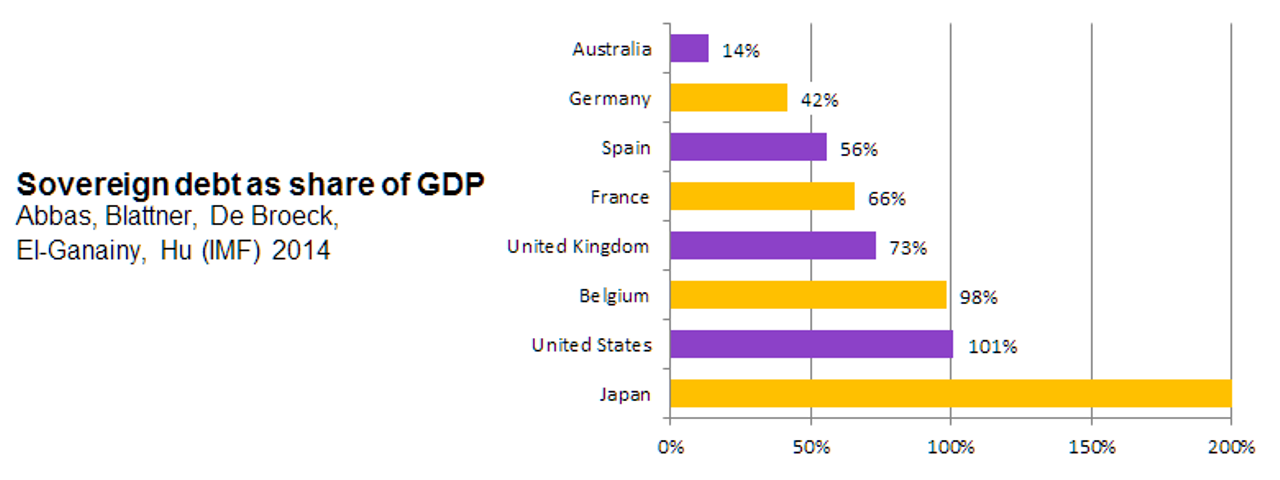

Private sector debt accumulated before a crisis often morphs into public sector debt … debt either moves up the economic food chain, or governments take on new debt to cushion the burdens of existing debt. Whatever the mechanism, the effect is the same: unsustainable levels of sovereign debt (p304).

In the future, central banks must proactively use monetary policy and credit policy to rein in and tame speculative bubbles (p274).

The end of Russian communism provided the most dramatic example of unconstrained capitalism last century, when the west ignored its own long history of incremental development and encouraged an overnight shift to free markets. Without time to build institutional infrastructure and capacity, the result was shocking but predictable. A tiny minority got very rich while the average person’s life expectancy fell by ten years.

By contrast, China’s steady state-led transition from socialism has produced faster growth than the original revolution of capitalist industrialisation. Historical evidence confirms that large and effective governments also create stronger economies in developing capitalist nations (Ha-Joon Chang).

Social equity and mobility

The state is also the critical redistributive institution, particularly today when global corporations maximise the share of their productive returns which can be passed to shareholders and executives, and minimise their taxes. The American example of hands off government shows how far capitalism can reduce social equity and mobility, even in the richest nation in the world. In contrast, nations with strong traditions of tolerance, democracy and social safety nets have much better results for both equity and mobility.

Over the last thirty years the importance of equity has been forced out of public debate by finance-driven economics, but the latest research from the International Monetary Fund confirmed that countries with lower inequality tend to experience higher and more stable growth, while the growth benefits of lower inequality are typically greater than the growth costs of the redistributive measures to achieve them (Ostry, Berg and Tsangarides).

So how far could we increase equity? The original Marx said “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” and this remains an inspiring ideal. For economic policy though, we need practical and achievable targets to maximise the benefits of capitalism’s productive efficiency. There is no proven setting for equity which will guarantee a balance between incentives for capital and labour, but normal profit is defined as the average rate received by productive enterprises in competitive non-monopoly markets. The best modern approximation of competitive markets was around 1980, providing a practical benchmark for equity. In 1978 the ratio of CEO to average wages in America was 30:1, today it is 300:1.

“Class perspective” Better government through tax-funded elections:

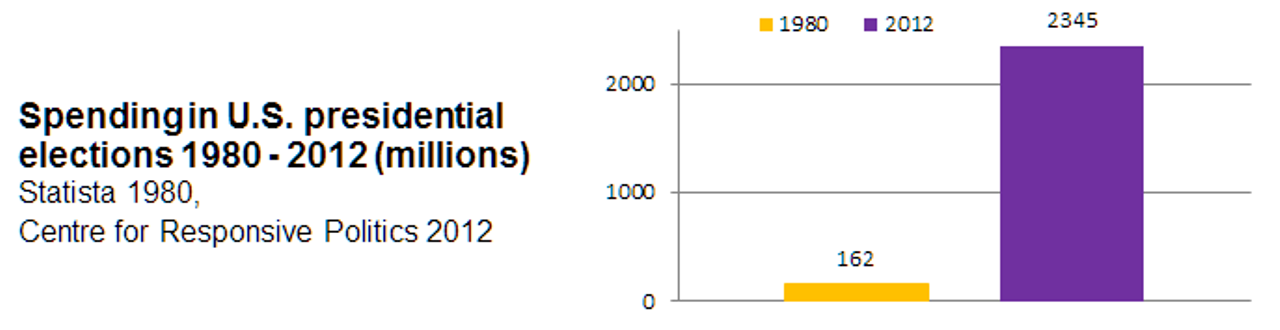

In many countries today, political donations and hidden transfers have handed control of key government economic policy to capital. The class perspective reminds us that institutional incentives shape the actions of their participants, and government is no exception.

If nations allow unlimited political donations, as America does, government will be run for the benefit of the largest corporations. In today’s globalised world, even dictators can buy articulate public relations teams to neutralise media and public scrutiny. The only policy which structurally incentivises political transparency over the long term is to fund political parties and elections from taxation, using clear and equitable rules.

Also from the perspective of structural incentives, when political systems have too many levels or too many parties, they struggle to make decisions and the public become disconnected from politics, leaving policy to be dominated by paid staff in political parties and their backers. My home country New Zealand has one of the world’s most effective systems, with a single house of parliament and a fair form of proportional representation which still ensures parties have to be large enough to compete across a substantial share of all electorates, and reserving seven seats for indigenous Maori representatives.

Structural misincentives

All forms of government have strengths and weaknesses due to their internal classes, including political party employees, state service managers, senior advisory staff and operational staff. These groups can have significant power precisely because their decisions have important consequences in the economy.

In Australia a new class of enthusiastic middle managers recently joined the public service from the private sector, keen to advance their careers by implementing the market-first approach of an incoming conservative government. The traditional public service culture emphasising stability and continuity over change was replaced by uncritical implementation of the latest party agenda, a trend reinforced by job cuts in the post-2008 budget cuts. There were also positive and overdue changes though, since Australia’s multi-level political system holds back policy development.

The European Union works well for its stronger nations, who benefit from a lower averaged exchange rate, but fails the smaller member economies. Without separate national currencies to keep their industries competitive, they are reduced to migrant labour sources. The EU’s central bureaucracy then prioritises repayment of issued debts regardless of the economic prospects of its poorer member nations. Historical evidence suggests exit from currency unions may be the best option to retain jobs in small poorer nations (Rose), while remaining part of the common market. In the long term, new and fairer forms of regional currency exchange need to be developed.

America exemplifies the leadership model of democracy, where a single person is the public face of government policy and the executive dominates decision making. Reagon (1980) and Thatcher (1979) were able to completely transform social policy through privatisation and deregulation, despite the risks of these unproven strategies. The rapidity of these changes showed how weak their institutional and democratic checks and balances had become.

Chart 11: Change in US electoral expenditure, 1980 to 2012

The election cycle also provides a strong internal incentive for policies which deliver quick results. Governments in both rich and poor nations are reinforcing this trend by expanding teams which specialise in polling, data analysis and manipulating public messages. The resulting short term priorities increase our long term economic and social instability.

And governments naturally tend to be pro-growth since economic growth increases taxable income. Stimulus which creates net value has a place, but excess stimulus just creates bubbles and increases debt, reducing the state’s capacity for future economic support. Stimulating housing in particular has led to excessive investment in high end housing and neglect of affordable housing.

Governments are primarily funded by taxation, but after the 1980s debate on the merits of tax forms became largely ideological. Governments were demonised as inefficient and taxes reduced. Since the global financial crisis bailout, corporate tax avoidance has shot back to the top of the G20’s global agenda. Despite this push for internationally coordinated reform from most developed nations, financial penalties on short term capital flows were over ruled by the United States, then by the United Kingdom in the European Union.

National governments’ emphasis remains on the efficiency of tax collection, rather than equity and new incentives to reshape the economy. Regressive consumption taxes threaten to replace corporate taxes, further dampening consumer demand.

“Boomerang” Michael Lewis:

I had gone to see Germany’s deputy minister of finance, a forty-four-year-old career government official named Jorg Asmussen. He was a type familiar in Germany but absolutely freakish in Greece or, for that matter, the United States: a keenly intelligent, highly ambitious civil servant who had no other ambition but to serve his country. His sparkling curriculum vitae was missing a line that would be found on the resumes of men in his position almost everywhere else in the world—the line where he leaves government service for Goldman Sachs to cash out. When I asked another prominent German civil servant why he hadn’t taken time out of public service to make his fortune working for some bank, the way every American civil servant who is anywhere near finance seems to want to do, his expression changed to alarm. “But I could never do this, “ he said. “It would be illoyal!” (p144, Lewis)

There is no free money

Once, the value of coins was the value of their metals but today money depends on the credibility of national financial institutions and policies. Currencies are sold up or down according to capital’s assessment of each nation’s current and future prospects.

The temporary exception is those countries powerful enough to ignore global financial governance conventions, large enough to make markets cautious about the risk of systemic collapse if they pull out capital, and with sufficient reserves to defend their currency. America, Japan and the EU can print more money, depreciate their currency, watch exports expand and share markets soar.

This is partly a confidence trick, relying on public suspension of disbelief. Printing money does benefit shareholders in America, Germany and Japan in the short term, but it has many short and long term trade-offs. Like all forms of stimulus, money printing will add to future government deficits. At some point central banks have to return the money supply to normal, which requires selling the assets they have purchased. Krugman’s conservative estimate compares the purchase of long term 10 year bonds in a low interest environment with rates 2.5%, to sale when interest rates are closer to the long run average of 6%, where each $1T of quantitative easing produces a loss of $240B. If interest rates are higher, reflecting a future environment which recognises higher investment risks, central banks have to sell riskier assets into a falling market and losses could be much larger.

More critically, the purchase of assets with printed money forced investors into riskier purchases to maintain returns on their capital—and with the enormous losses of 2008 still on the books, corporations are not investing for productivity, banks are lending less, consumers are saving more. When the share market reaches its peak, everyone will pull their money out at the same time and find there’s no safe place left to invest. Crises, corporate and sovereign defaults will force a sudden return to high interest rates.

Chart 12: Sovereign debt

“Class perspective” Who wins when the free money runs out:

“There is no free lunch” and “The price of debt rises with risk”. These are two fundamental beliefs of modern economics, so why is interest-free debt created by government money-printing the defining characteristic of the early 21st century?

Private debt purchasers can suspend their disbelief, but this will last exactly as long as they find high short term profits in the associated market volatility. A decade of easy money, picking the short term winners and losers, is more appealing than re-balancing economies in a global slowdown. That slowdown will arrive sooner or later though, whichever path is taken, since it is driven by fundamentals—falling capital investment and productivity, increased state and private debt, the demographic shock of ageing populations with falling birth rates, and natural resource limits. And with more debt in an already debt-ridden world, the crisis will be more severe.

These are the main winners and losers from today’s cheap debt:

- Powerful nations launched state money-printing, gaining from lowered currencies;

- All nations had to follow into debt and rising risk to compete in this export-driven era;

- All investment is forced towards short term gains and riskier forms of capital;

- Financial capital benefited from stable low interest, growing again after the GFC;

- Today’s rich avoid tax more easily in free financial markets;

- Western retirees either getless interest income or take risks they cannot afford;

- National crises will trigger capital flight to rich nations and sharp rises in interest rates;

- Developing nations will suffer most as their states and businesses are more vulnerable;

- This long boom/bust cycle will leave next generation’s workers to face massive job cuts;

- Transnational corporations will increase market control in crises, unless states intervene.

National and international conflict

On to peppery and waterlogged countries!—at the service of the most

monstrous industrial or military exploitation. Farewell here, anywhere.

Well-meaning draftees, we’ll adopt a ferocious philosophy;

ignorant of science, sly for comfort; let the shambling world drop dead.

This is the real march. Heads up, forward!

—Arthur Rimbaud, Democracy (1886)

Government includes military forces, another sector which transfers value out of the productive economy. Historically, there is no doubt that military and paramilitary elites created hierarchies with cohesive classes which extracted a toll from productive income in conquered nations. Powerful nations still retain strong traditions favouring their military, deeply ingrained from those earlier eras when the wealth of nations came from overseas theft through force of arms.

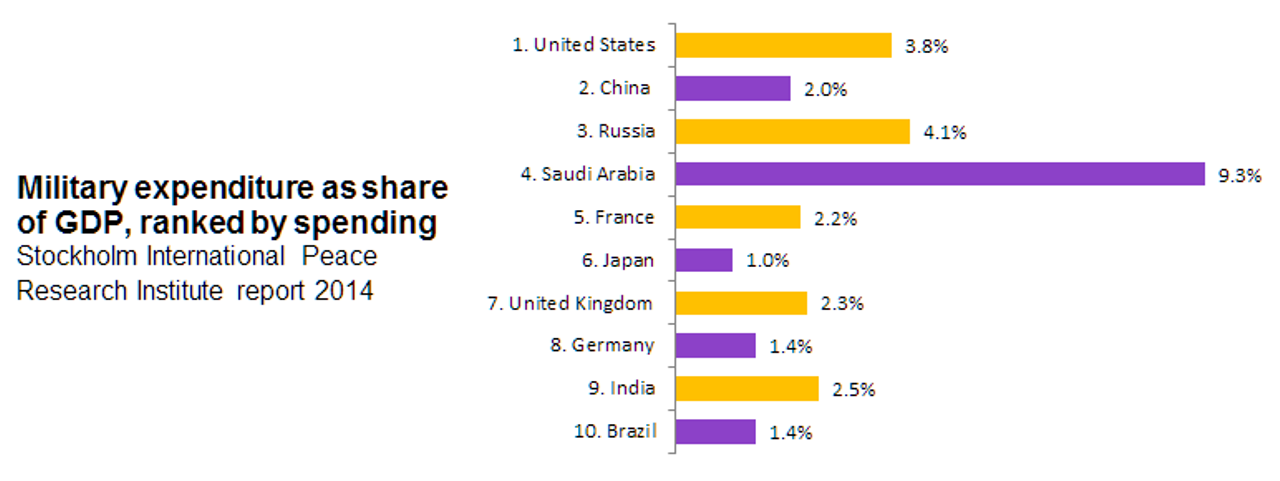

Today’s largest modern armies also create profits from their monopoly of high technology weapon sales and the resulting international instability. By the time modern-era technology and international economic integration removed the potential gain from aggressive wars of conquest, public debate on improving cooperative conflict resolution had died out. American-led unilateral initiatives filled the gap, barely hiding their underlying economic self-interest, and arms sales continued to undermine national stability.

If today’s aggressive rich powers stopped unilateral actions and ad hoc military coalitions to support better international responses through a more effective United Nations, conflicts would reduce and more money could flow back to the families of soldiers from developing nations. Military training time could be reduced over time as conflict was reduced, supplemented by development and disaster recovery training and deployments to create genuine skills and post-army employment prospects.

Class has another link to armed conflict too. The creation of a new class of international terrorists in Iraq prisons, in militarised Israel and Palestine, in developing countries dominated by foreign exploiters of natural resources is never justifiable. Short term military and corporate objectives will not deliver social benefits to balance the long term costs of creating a generation of well organised armed terrorists.

The depth of hardship created by war is impossible to convey here, but understood by most people. Violent interventions destabilise whole regions for generations. We have an opportunity since the price of unilateral war is harder to fund today and the mobility of international terrorism is harder to counter. We also have a legacy of semi-autonomous military command hierarchies and significant public enthusiasm for military nationalism. In an uncertain global economy, the prospects for peace are equally uncertain.

Chart 13: Global military spending

“Class perspective” Who won that war?

The distribution of suffering and advantage through war will extend across a very long timeframe. Remember the brash 2003 pronouncements of Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz ahead of the Iraq war; “Something under $50 billion for the cost” and “We’re dealing with a country that can really finance its own reconstruction, and relatively soon”. The best estimate for Iraq is now $4-6 trillion (Bilmes, 2013); the United States has yet to reach the peak year for veteran on-costs from even the Vietnam war; Australia recently costed the resettlement of 12,000 Syrian refugees at AU$700 million.

To really understand the distributional effects of war requires uncovering all the costed and uncosted consequences:

- Civilian death and injury; lost communities, homes, jobs, capital; traumatised adults, children;

- Destroyed productive capital and skills, destabilised and degraded national governments;

- Armed forces deaths, injuries and long term rehabilitation;

- Family support for veterans; depression, suicide, drug, alcohol, spouse and child abuse;

- Refugee support, long term resettlement and training;

- Direct terrorism deaths and injury, indirect costs of security, policing and border contol;

- Opportunity costs from lost investment, eg cost-effective infrastructure, good government;

- Economic distortions, inefficiencies, costs, eg higher oil prices after the Iraq war;

- Perpetuating inefficient trade dependencies, eg Russian threats against Ukraine EU entry;

- Lost disaster assistance capacity due to the military’s emphasis on combat, necessary or not;

- Enormous rewards, pre- and post-employment, for military-industrial executives and politicians;

- Lifetime prestige to senior military staff and military-industrial employees and their families;

- Non-combat veterans in rich nations, mostly men, receive good wages and excellent pensions.

Military forces always rely on extreme hierarchies. The privileges for higher ranks are enormous and the risks zero, the life of basic recruits is tough and the risks occasionally high; yet most veterans still support the military institution. Unfortunately, our lifecycle-centred human way of learning coupled with such a dominating culture closes minds to the bigger picture of social cost-accounting. It’s natural to feel “I’ve become a stronger person through my life; my character was forged in the military; therefore, the military is necessary and just”. And many recruits will never experience war, receiving a generous lifetime package with higher, earlier pensions in Australia, or extorting kickbacks in countries with weaker government.

Foreign military bases around the world provide intelligence and logistics to support unilateral interventions. American leads the list with bases in 31 other nations, followed by the UK in 17, France in 15, Italy and Russia in 9 and Turkey in 6 (Wikipedia). Military bases played a key role in recent international conflicts including Russia’s annexation of Crimea to protect its Black Sea Navy base and Syrian interventions to protect its Mediterranean Navy base at Tartus. Foreign bases also build long term support for the military culture and lifestyle, in the owning country through lucrative overseas postings and in the host country by integration with the local economy and community.

Drones are the military’s latest strategy: fewer troops, but more unmanned aerial strikes. Predator drones alone have flown more than 80,000 missions in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia. When do these operations constitute a war? This robotic warfare makes it easier to run covert unofficial attacks without a declaration of war or political oversight, and kills innocent civilians, ensuring a long term stream of recruits for militant groups. Unless their use is subject to scrutiny, drones are making the world less safe.

The Iraq war was novel in another way too, marking America’s first return to debt-funded war since France financed their War of Independence. Financing wars normally requires up-front increases in taxes but the United States cut taxes in 2001 and 2003. The costs of this war will be paid by future taxpayers.

The United States dominates the global security debate, spending far more than any other country on military spending per capita and around 20 percent of its total federal budget, nearly six times more than China and 43% of the entire global military spend (SIPRI 2011). As a consequence of its recent wars, 24% of United States adult males are veterans of the armed forces (Gallup January-October 2012), so don’t expect positive new global security strategies to be American led.

We need to re-evaluate the past and consider new strategies for the global security environment in which modern wars take place:

- Expelling Iraq from Kuwait showed direct annexations are more vulnerable, so less likely today;

- America’s military elite favour unilateral action but miscalculate the costs and consequences;

- The Iraq invasion boosted international terrorism and its future cost to the whole world;

- Israel’s planned but unacknowledged annexation of Palestine has similar future costs;

- The United Nations, under funded and ineffective in recent years, needs revitalising.

And finally, consider another layer on top of all these direct military considerations. Add the consequences of a future global economic slowdown and crises, the increased share of shrinking global wealth which corporations and powerful nations will horde in harder times, and rising border tensions. Improving the governance of our global conflict resolution will be more important than ever in the 21st century.

Global government

For the last thirty years floating exchange rates backed by currency reserves in US dollars have allowed America to pursue and promote bad policy yet still be the beneficiary of capital flight in every crisis. The west presents its wealth and dominance as the result of more developed state institutions but our museums and histories show that strong modern governments were built on a foundation of military plunder in weaker nations, a middle game enforcing unequal trade arrangements, and an endgame of foreign ownership and control.

Global institutions of government regularly prescribe platitudes for developing nations—free trade for growth, free capital markets, flexible exchange rates, repayment of debts—rules which favour large rich economies and a very different path from their own successful development. Ironically, after the global financial crisis these leading economies found their own prescription for others was now optional at home. The rhetoric of flexible exchange rates is forgotten as they print money to lower their currencies, while the European Union gives priority to its richest nations’ banks and pushes austerity for its struggling smaller member nations.

Multinational trade deals like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) have become secretive lobbying vehicles for global corporations to press for new privileges like direct action against states which limit their profits by protecting employment, the environment and health rights. The deals are intended to boost western business’s “ability to compete with states” and limit “politicians’ real impact on the economic life of a country”, in French CEO Bernard Arnault’s approving words.

The International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) are likely to be expanded in future crises, making it the next global creditor of last resort, but the IMF is notoriously undemocratic. Voting is one vote per dollar, giving the US an effective veto since it holds 18% of the shares and decisions require an 85% majority. Support will come with conditions; reduced national control of economic policy and a focus on debt repayment.

In hosting the Group of 20 summit in 2014, Australia has added new commitments including a mammoth infrastructure program along with health and education spending cuts and privatisation, despite doubt over parliamentary support. Other nations made similar G20 commitments to restart growth which will be reviewed by officials from two member nations and evaluated annually by the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Western advocacy for opening China’s financial markets is the latest example of corporate self-interest. The Chinese population has much more to lose than gain from western expertise at circumventing limits on business, and with plenty of internal capital there is no need to allow foreign investment to send a larger share of future profits overseas. Gaining expertise through limited partnerships will prove much more rewarding.

All nations need to scrutinise these international deals much more closely; too many have taken wealth out of nations into the corporate ether where tax has been redefined as optional. The 2012 UNCTAD report shows the British Virgin Islands, a tiny tax haven, receiving more foreign direct investment than the entire United Kingdom.

“Boomerang” Michael Lewis:

Kyle Bass, manager of a hedge fund called Hayman Capital, made a massive wager against the subprime mortgage bond market. He was now rich and even, in investment circles, a little famous. But his mind had moved on from the subprime mortgage bond debacle: having taken his profits, he had a new all-consuming interest, governments. They were no longer talking about the collapse of a few bonds. They were talking about the collapse of entire countries.

And they had a shiny new investment thesis. It ran, roughly, as follows. From 2002 there had been something like a false boom in much of the rich, developed world. What appeared to be economic growth was activity fuelled by people borrowing money they probably couldn’t afford to repay. The public debt of rich countries already stood at what appeared to be dangerously high levels and, in response to the crisis, was rapidly growing. But the public debt of these countries was no longer the official public debt. As a practical matter it included the debts inside each country’s banking system, which, in another crisis, would be transferred to the government.

“The first thing we tried to figure out,” said Bass, “was how big these banking systems were, especially in relation to government revenues. We took about four months to gather the data. No one had it.” The numbers added up to astonishing totals. Historically, such levels of government indebtedness had led to government default. Still, he wondered if perhaps he was missing something. “I went looking for someone, anyone, who knew something about the history of sovereign defaults,” he said.

He found the leading expert on the subject, a professor at Harvard named Kenneth Rogoff. “We walked Rogoff through the numbers,” said Bass, “ and he just looked at them, then sat back in his chair and said, ‘I can hardly believe it is this bad.’ And I said, ‘Wait a minute. You’re the world’s foremost expert on sovereign balance sheets. If you don’t know this, who does?’ I thought, Holy shit, who is paying attention?” (xii-xiii).

Government: Future prospects

Complex economic incentives within the institutions of all nations have limited the capacity of today’s governments to deliver stability and equity, yet good government is essential to achieve these critical outcomes. With debts accumulated from the 2008 bailout, pressure to privatise assets and demands for endless stimulus, nation states are now weaker and transnational corporations are much more powerful. Either societies invest more to secure the independence, viability, quality and responsiveness of government or live with the consequences of unconstrained markets, instability and inequity.

We are now entering a dangerous cycle where governments are expected to sell off strategic state enterprises, handing over natural monopolies to be milked by private corporations and further reducing the state’s income and viability. Consumer costs will rise and expenditure will fall, jobs will be lost and taxes shrink. Governments are also under pressure to subsidise business with potentially unsustainable infrastructure projects to boost growth. If we continue on this path, government will be permanently weakened and a far more dangerous capitalism unlocked.

To avoid further crises, national and international regulation needs to shift incentives towards rewarding long term investment while discouraging speculation and instability. Governments need to add counter cyclical tools to their agenda, holding back booms from becoming bubbles. State assets need to be retained to avoid monopoly producers and help fund the government. These are not easy policies to sell since they don’t engage the public, while attracting instant opposition from corporations.

There’s a lot at stake here and far too little open discussion of the options. In this climate of limited global leadership, building effective economic models in developing nations may be the best short term strategy to minimise the costs of global instability. Asian regional blocs of nations could become critical innovators to protect themselves and force changes on the international order, retaining the benefits of productive national investment for both local capital and local workers.

Developing nation blocks will still favour big nations over small, corporations and state monopolies over social equity, so workers also need to improve their organisational strength, communities need to increase their political influence, women need increase their public power and influence if long term equity is to improve in these difficult times.

Government: Priorities for equity

- Rebuilding support for increased government capacity, the value of economic regulation and state ownership of natural-monopoly assets, equitable tax revenues, countercyclical stimulus and restraint, sustainable use of natural resources;

- Funding elections from taxation not corporate lobby groups;

- Promoting evidence based economic models in developing nations, reducing corruption and increasing the capacity and governance of economic and social institutions;

- Democratising global governance institutions and/or creating new regional alternatives;

- Developing international capacity to limit wars and end unilateral military interventions, diversifying military training into disaster responses;

- Minimising global financial and commodities speculation;

- Providing legislative, institutional and cultural support for effective unions, gender and racial equality, social equity and class mobility.

The boom, not the slump, is the time for austerity at the Treasury.

—John Maynard Keynes (1937)