Nature

The greatest book of all is the book of Nature, forever open and forever worth reading. Every other book is a version of this one, riddled with the errors and interpolations of man.

—Antonio Gaudi (1852 – 1926)

Humanity’s impact on nature is also brought into sharp focus by analysing our work extracting and consuming resources and the resulting social transfers. These transfers take two main forms. The first is corporate and state exploitation benefiting the powerful; the second are long term social transfers from sustainable use by future generations to wasteful consumption today. Spending time in nature, paying attention to the declining capacity of our environment to support diverse habitats including our own, is a powerful reminder that long term changes are much more important than short term gains.

Today we are so far away from a sustainable path, so out of touch with natural balance. Take some time to reflect on the perspective of a much older culture which had firm roots in the physical world. These extracts are from “Gurindji Journey”, stories told to Minoru Hokari by the Gurindji people of Daguragu and Kalkaringi in northern Australia.

“An Indigenous perspective” Living in Gurindji country:

The Gurindji people, especially the elders, often sit on the ground and do nothing for a long time. I thought they were doing nothing. It took me a while to realise that they were actually seeing, listening and feeling. If you want to know what is happening in this world, you should stay still and pay attention to the world. Be aware of what is happening around you. Do not make your own ‘noise’, which often fogs your senses.

I usually try to understand the world by asking and searching. However, Gurindji people demonstrated to me how to know the world by simply being still and paying attention. The art of knowing is not always the way of searching, but often the way of paying attention.

Paying attention is also essential when the Gurindji people practise their history. Paying attention to the world means not only knowing what is happening, but also remembering what happened here and there. The Gurindji people do not search for history as most academic historians do. Instead, they pay attention to their history.

For instance, you drive a car to visit your family in another community and see a hill, and you remember (or you hear the elders’ teachings or discussion) that old people were killed there by kartiya [whitefella] in the early days. History should be listened to, seen and felt around oneself in everyday life. History is something your body can sense, remember and practise.

In addition, the Gurindji people often draw diagrams on the ground to explain their history. For them, all bodies, objects and landscapes contain memories. According to the Gurindji people, the world is full of life. In fact, it is not easy to find non-living beings in this world. Dreaming or ancestral beings are all alive in the world too. They include stones, hills, rivers, waterholes and rainbows as well as animals, insects and plants.

What is probably more important is that the earth itself is alive too. Jimmy Mangayarri told me this. He picked up a handful of sand and taught me that you may think this janyja [soil] was just soil, but this was a ‘man’. He also said the earth tells you the ‘right way’. Furthermore one of Old Jimmy’s favourite sayings was, ‘Don’t matter what it is, everything come out longa this earth.’

When Old Jimmy says that everything comes from the earth, he means that everything was created and has been maintained by the earth. To describe this, Old Jimmy often used the following five different words: ‘earth’, ‘Dreaming’, ‘law’, ‘right way’ and ‘history’. Traditional aboriginal Dreaming stories tell you not only about the origin of the world, but also about how the world has been maintained. Dreaming teaches us how to look after this created world. The Gurindji people have been part of moral history because they have been participating in sustaining the world by following the Dreaming, or the ‘right way’. Landscape is also history because it contains visible memories and evidence that tell you that the world has been maintained.

History is not just the story of the past. The earth is always there. That hill has been there and should always be there. Dreaming is always active, and therefore this world should always be maintained. Therefore Dreaming is not just a story of the past; it contains the present and the potential future at the same time. That hill was there, is there and should be there for all time.

For a while, I thought the Gurindji people liked travelling, just as many settlers do. However I realised that their movement is normally not travel at all. Their mobility is not for getting out of their home but for living in their home. For the Gurindji people, ‘nomadic’ life does not mean a travelling lifestyle or life without a home, but it means life in a massive home, the traditional Gurindji country.

One of the reasons you have to move around the country is that Dreaming sites are scattered all over the country. The Gurindji cosmology is based on networking among many sites, countries and people. The world is maintained through the web of connection between Dreaming beings, people and their countries and ceremonies.

This view of Gurindji cosmology leads us to the unique positioning of ‘self’ in the world. First of all, ‘self’ as a living human cannot be the centre of the world. The Dreaming or ancestral beings are as alive as living human beings. Humans cannot exist if the Dreaming dies, because humans are a part of this living world that is sustained by the Dreaming. Humans not only maintain the world but are also maintained by the world.

Second, you cannot maintain your country by yourself, but only by connection with other people and their countries. Third, there is no one person, nor any institution, which can control the whole community by her/his/their/its own will. Decision making is the process of negotiation with one another to build a ‘connection’ among the people in the community.

As ‘self’ is relationalised through the web of connection, so knowledge is also relationalised. There is no one person, as well as no place, that generates exclusive knowledge. Some people and places may generate more stories than others. A person who has more knowledge and connection to other people and places may assert more authenticity over more stories than others. But because there is no authentic centre that guarantees the validity of information, knowledge naturally acquires many variations through the process of networking.

The Gurindji people’s historical knowledge accepts many different versions of events. Information running through the web of connection is rarely judged according to whether it is right or wrong. Multiple variations of information are produced, pooled and maintained as a bundle of possibilities without urgent judgement. This mode of knowledge system is not only open; it is also flexible. Knowledge or pooled stories are always chosen and used according to the context of the story being told.

In order to maintain their information system, it is important to spend an enormous amount of time discussing, learning, teaching and sharing. The open and flexible system of knowledge can function well only if people do not rush to make a decision. It was amazing to know how long people could sit down, discuss and negotiate an issue in order to explore every possibility of their decisions. In order to keep the knowledge system functioning, you should take as much time as you need.

Once a decision has been made, action follows immediately. After waiting two months for discussions about the ceremonial visit to Docker River, I thought it would never happen. However, when it happened, it happened ridiculously quickly. When they finally decided to leave the community, we were driving cars towards the south by the evening of the same day!

Depletion and rising costs

Some nations are still rushing headlong to degrade their environment by extracting short term resources like coal seam gas. Others are starting to think more carefully about the long term balance between human needs and a sustainable world. America is clearly desperate for growth at any price; China faces such obvious health costs from pollution that the government has to act. Smaller countries suffer most from rising commodity prices but have limited power in international forums to influence more powerful nations and corporations.

Regardless of our differences, the cost of extracting non-renewable energy will keep increasing and economic solutions have to be found by all nations. We need to change national and international economic policies, to move away from growth targets towards sustainable levels of production and investment which maximise our efficiency and our alternatives.

“The end of growth” Richard Heinberg:

What might a sustainable society look like? Assuming we do everything right, what could we achieve? How might the world look as a result?

The economy of the future will necessarily be steady-state, not requiring constant growth. It will be based on the use of renewable resources harvested at a rate slower than that of natural replenishment; and on the use of non-renewable resources at declining rates, with metals and minerals recycled and re-used wherever possible. Human population will have to achieve a level that can be supported by resources used this way, and that level is likely to be significantly lower than the current one.

But these criteria leave many details open to conjecture. What technologies could we develop and use under these conditions? Exactly what size of population would be sustainable? The supportable population size will also depend on how much we degrade soil, water, and climate before we achieve a condition of sustainability (p280-1).

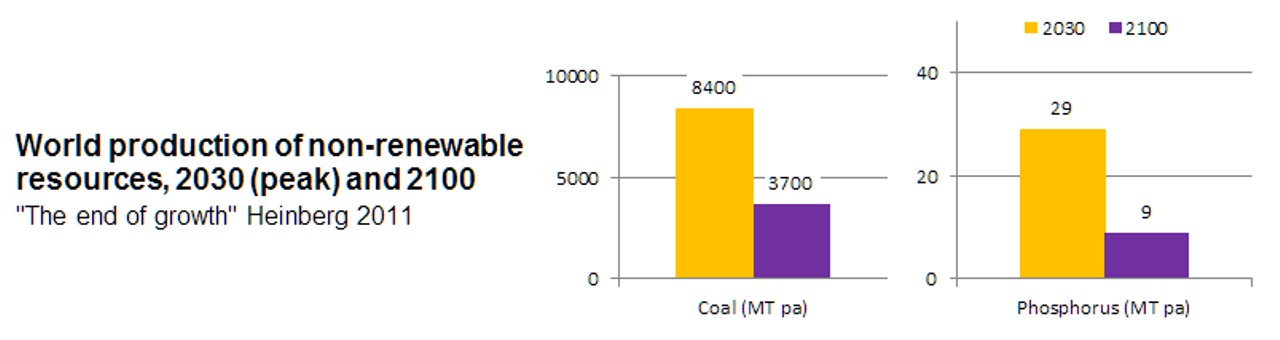

Chart 14: Estimated production of non-renewable resources, 2030 and 2100

Water is another finite resource where human use is increasing much faster than the rate of population growth. Water consumption has tripled over the past 50 years, with our annual requirement predicted to reach 90% of all available water in rivers, lakes and underground aquifers. Around 60 percent of the world’s population live in areas that receive only a quarter of the world’s annual rainfall.

The amount of global arable land has been relatively constant over the last decade at around 3.4 billion acres, but food production will need to increase by 60-70 percent by 2050 to feed the world’s population. Grain yields have tripled since 1950 but the rate of improvement is now falling as we reach technological limits.

“Class perspective” Exploiting nature is always a class transfer:

“Green accounting” applied to Africa’s national accounts shows wealth per person declining by 2.8% per year for 1970-2000. Resources have been plundered for elite consumption, without creating alternative investments to generate future replacement income streams (Collier, p121).

The story of planetary exploitation, like production and reproduction, is shaped by social transfers; historically from Indigenous peoples through land theft, on to today’s degradation of productive farmland for short term profit, and into global control of scarce and strategically important natural resources.

There are the obvious short term transfers which enrich governments, investors and sectors of workers, but discourage efficient large scale production because political corruption and instability create unacceptable risks for long term infrastructure investments. There are transfers between the developed and developing worlds, between political elites and citizens in developing nations.

Unsustainable short term exploitation today also lays a foundation for transferring costs to future generations, reducing investment to develop sustainable alternatives and increasing pressure for inhumane exploitation of animals and fish for food.

Nature: Future prospects

It’s remarkable that there is virtually no debate about what kind of world would be genuinely sustainable, even though we need to find radical new solutions to these problems this century. The best evidence today suggests human impact will push the natural world past a tipping point, creating long term climate change and economic dislocation. Debate about the cost of climate change has recently shifted towards consensus that the costs are impossible to model reliably but they are not excessive (fifth report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change working group three 2014).

Agreement is growing on the necessity to act now so that temperature rises may be limited to two further degrees, beyond which both uncertainty and risk become unacceptable (Heinberg). Agreement on how to achieve that goal is much harder, but the sooner we accept that growing affluence has limits, the sooner we will find stable settings for our economies and our resource use.

Government regulation is clearly essential to restrain monopoly and corruption, to keep resource use sustainable, to prevent speculative price instability. Economists also need to embrace sustainability and develop anti-cyclical market interventions. Growth targets are our problem not our solution for both the environment and the economy, yet the idea that good economic management could mean zero or negative growth rarely appears in mainstream debate.

Communities face an enormous challenge to put sustainable long term economics back on public and government agendas. Family and community life is also far less in touch with nature today—a majority see our natural world only from a car stop or on digital media, a minor diversion from busy working lives. Reclaiming more time out of the city encourages a balanced perspective on what’s important in both the natural and human worlds; we may reserve more time for family, friends and recreation. Seeking solutions for global problems can have personal value too.

Nature: Equity priorities

- Rebuilding support for government regulation and equitable tax revenues, stable economies and sustainable use of natural resources.

- Reducing corruption in developing nations, which undermines long term investment in sustainable natural resources.

- Democratising global governance institutions and/or creating new regional alternatives.