Home and Family

We’ve begun to raise daughters more like sons… but few have the courage to raise our sons more like our daughters.

—Gloria Steinem (1983)

Families recreate each new human generation, but our families, lives, skills and personal health are themselves shaped by social institutions and culture. And as in production, relationships between couples, parents and children, extended families and networks create a complex division of work and rewards to sustain human societies.

While pregnancy and birth naturally introduce gender differences into the lives of all parents for a short period, gendered social inequality is not natural. It is created by each nation’s complex blend of differences in family organisation, workplace equality and social equity, and recreated in new forms by each generation.

The importance of gender differences is underrated in a world dominated by men and money, but gender divisions are an important determinant of national wealth and life satisfaction. Any framework for understanding social institutions and social change has to consider the family, and work-family interdependence.

My friend Christine says “The material benefit of patriarchy is as obvious today as it was when I was a teenager”. So why is feminism hardly talked about in the west today? Christine works in the community support centre of a working class neighbourhood, while a majority of wealthy western women do well under the modern gender divide. The lives of working class women like those who visit the centre are largely ignored in public debate.

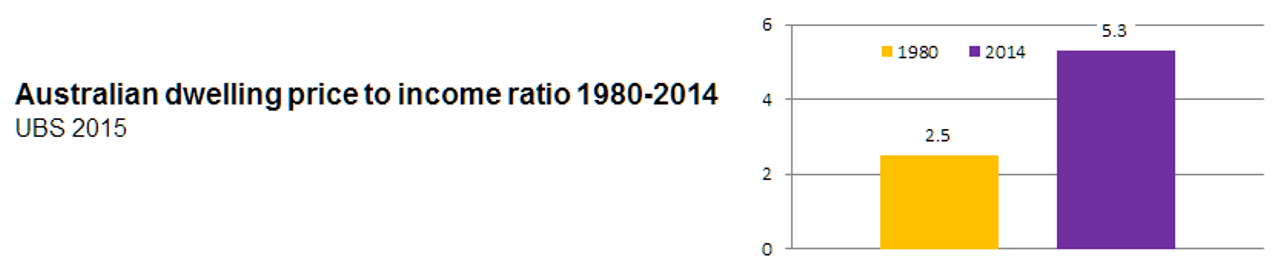

On the positive side, time use surveys show that, on average, Australian fathers and mothers now have nearly equal total hours of work. This generation’s women are more involved in paid work and men contribute more to unpaid domestic work. The gender wage gap has been declining in the west as women’s higher workforce participation delivers financial gains.

Chart 8: Average male and female wages, retirement savings, paid and unpaid work hours (Australia)

But western birth rates are declining too, confirming more mothers are not finding the combination of increased workforce participation and parenting satisfying. And exported jobs, youth unemployment and crises mean the next generation will have less access to meaningful work. Home ownership is less affordable, removing younger families’ most important means to accumulate family capital for a comfortable retirement. In the US with its low social mobility the change is particularly marked; parenting rates for middle and upper class families have fallen so far that a much higher percentage of children are now born into poor single parent families.

The traditional lifetime balance of trade-offs between parent and child in rich nations has shifted. Children still need long hours of parental assistance and guidance in their early years and education costs today’s parents much more, but longer working lives and higher incomes have radically reduced the need for adult children to return support to their parents in old age. The internationalisation of careers, increased work hours and intensity, the separation and commercialisation of parent’s and children’s entertainment and many other changes also combine to weaken cross-generational family bonds. Parenting has become less rewarding in today’s world.

My emphasis here is on gendered inequality in a developed western economy since I live in Australia, but this structured approach to gender analysis can be adapted to the varied cultures of each nation, their particular stage of development, the vast differences in every nation’s social institutions and the diversity of the lifecycle stages which reproduce each new generation. As in section one I’m asking at each stage of family life, how is the work organised? what are the transfers? who benefits? who shapes our “personal” lives?

This second section is quite detailed and anecdotal compared to section one on Production, reflecting the complexity of our life-cycle. Through all the many stages of our long lives, each of us gradually gets closer to understanding that tiny slice of the greater world which we personally inhabit. This natural learning lifecyle guides each individual well along our unique path, but is much less effective at showing us the big picture.

We all collect conditioning along the way from the gender we grow up in and the classes of work which provide our income; we draw conclusions from the narrow slice of life we have personally seen; we treat gender differences as natural rather than the result of specific trade-offs in roles and rewards passed down the generations; we get bogged down in the demanding challenges of working life, weakening our relationships at home; we grow old and forget the struggle facing youth; and men and women with social power and influence learn through the passage of their personal lives to portray this only as fair reward for hard work.

Applying a common approach which emphasises the complexity and interdependence of productive and reproductive class roles reminds us that the ways we organise work in families and factories are both crucial contributors to today’s global inequities.

Part 1 Stages over the reproductive lifecycle

Independent single adults

Today young adults stay at home longer, study longer at greater cost to parents and themselves, and join the workforce later with lower access to quality jobs than their parents’ generation. With interaction now mediated through commercialised entertainment, young people are less connected to their family, their community and their cultural history. Social skills and knowledge are less diverse, less practised and therefore less developed.

Couple relationships

Couples without children still have to negotiate a world created by gendered social expectations and institutions. Boys are schooled to value competitive sport which translates to time-wasting as passive spectators when they start work. Girls are schooled to pursue appearance which translates to purchasing “lifestyle” as adults.

A majority of male-female relationships still involve traditional gendered trade-offs—male as main earner, for increased leisure time and toys; female as main parent, for reduced career pressures; beauty, for a richer husband with lower expectations of the female partner working; women providing emotional support work and men talking sport. The resulting power imbalances make women’s lifetime prospects less certain, with today’s heterosexual partnerships much less likely to last a lifetime.

Same sex relationships are gradually edging closer to legal equality but are still culturally marginalised rather than supported, despite social benefits (reduced population pressure on shrinking natural resources) and personal benefits (no risk of pregnancy, no parenting costs, less relationship trade-offs to fit gender stereotypes).

Unpaid domestic work

Unpaid work is just as necessary as paid jobs but the dynamics are very different, especially for couples who have to negotiate their personal balance under the shadow of less flexible paid-work constraints. Hours of domestic work by women have been declining since the 1960s while men’s hours have been increasing. In the most recent Australian Time Use Survey (2006) the gap between women and men was down to 17 minutes per day, but total hours worked by couples are increasing.

Peer and recreational pressures

Cultural gender stereotypes encourage competition above cooperation and favour attractive girls and physical boys, giving a minority more attention therefore confidence and skills to assist them throughout life, and disadvantaging the majority born with average physical attributes.

Sexuality

More effective birth control and increased economic and social independence within the family have increased youth’s control over their sexuality. With its mix of satisfaction and vulnerability, sex continues to be associated with beginning a long term relationship, but an increasing minority defer commitment.

Australian studies have found a larger majority of men in heterosexual relationships described sex as very or extremely physically satisfying (90% vs 79% for women). This contrasts with homosexual relationships where only 86% of men but 93% of women described sex as very or extremely physically satisfying. Similar variations were recorded for emotional satisfaction (Richters Grulich de Visser Smith Rissel, 2003).

This satisfaction gap shows gender stereotyping intrudes on equal enjoyment of sex, with boys still pursuing girls for sexual experience but with too little interest on building good relationships and too little responsibility for possible children, while girls are torn between pursuing good providers and good relationships. The gap has narrowed though since early feminist Shere Hite exposed the gulf between American male and female sexual satisfaction in 1976.

These are all unusually high satisfaction rates for a social survey too, so we can safely conclude the obvious, that sex is usually fun and helps us offset the burdens which economic inequity imposes on our personal lives. The most recent evidence though shows a big drop in the proportion of women experiencing orgasms and the frequency of sex (Kontula, 2015) which is likely linked to the increasing work pressures of modern life.

Sex for sale

Commercial sex and supported mistresses are widespread in countries with traditional gender roles, while exploitative internet imagery is accessed by a significant proportion of our population. Both extract resources from families and undermine longer term relationships.

Sexual violence

With gender inequality comes abuse. A 2013 UN study reported that on average 30% of women reported physical or sexual violence by their partner, while for example 50% of Chinese men admitted physical or sexual abuse of their partner and 72% of Chinese rapists suffered no legal consequences. Even in comparitively wealthy countries, most policing still treats relationship violence as “domestic”, requiring the partner as witness rather than placing the obligation on police to gather evidence at the crime scene and prosecute.

Separation

As women’s working hours increase and employment security declines, differences in who does what work at home are more likely to create pressure and conflict rather than diversity and mutual satisfaction. It’s not easy to maintain a balanced and supportive relationship among today’s gender conventions and the proportion of single parents is still climbing (NZ Census 2006-2011). To provide a safety net, rich countries increasingly regulate for relatively equal division of resources and child support after separations.

Pregnancy

Time off work during and after pregnancy is reducing, a trade-off by women to pursue increased employment equality in the workplace.

Birth

Patriarchal medical institutions are increasingly controlling the birth experience. Caesarean rates keep rising, hospital stays get shorter with less emphasis on supporting informed choices. Birthing a baby today today feels less like a vocation and more like elective surgery.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding rates and duration are reducing as the health system shifts from primary to institutional services, with subtle but long term impacts on child health.

Parenting

Parenting time—imparting interpersonal skills and social knowledge to children—is reducing, replaced by far less subtle commercial television, computers and internet entertainment. Tomorrow’s children will be more susceptible to systemic commercial manipulation.

Childcare by grandparents has increased as more couples enter paid work and life expectancy increases. Paid childcare is growing, reducing parenting time and family closeness, increasing parents’ working hours to meet the cost.

Renting a home

Rental costs for independent living have increased relative to today’s youth wages, while job security and future prospects have reduced. High housing costs also provide a strong financial incentive for couple and group relationships, since a single residence is much more affordable with multiple incomes.

Owning a home

Housing tax policies in many rich countries have evolved to favour capital gain, driving prices up faster than wages and increasing home purchase default risk in downturns. Younger people have less access to secure meaningful work today and home ownership rates are falling, removing their most important means to accumulate family capital for stability and a comfortable retirement. The cost of housing also segregates rich from poor in separate neighbourhoods with vastly different services and opportunities, undermining equity and social mobility.

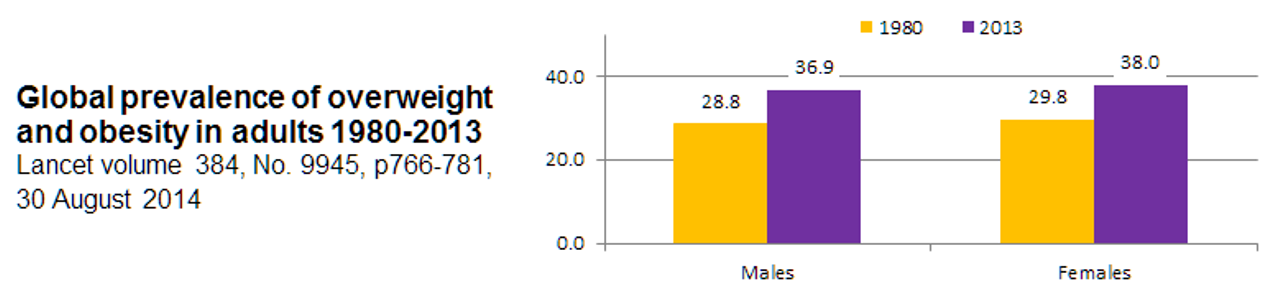

Chart 9: Cost of home as proportion of annual income, 1980 and 2014 Australia

Separations with children

Women head the vast majority of single-parent households and provide the majority of parenting hours when separated couples share parenting, reinforcing a life-long gap in male-female earning and retirement savings. All nations struggle to ensure non-parenting partners provide sufficient support for their children and ex-partner. Despite this, women’s greater commitment to longer term family stability can still result in higher rates of home ownership for single women than men, if the law supports fair separation settlements (New Zealand Census 2006 age groups 20-65).

Cooking and diet

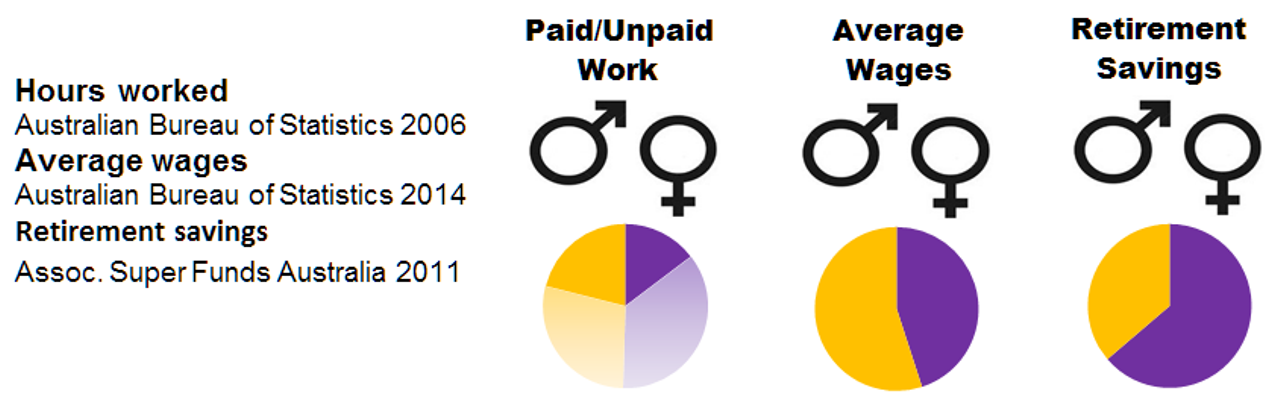

Reduced after-work personal time and lowered costs for purchased meals have combined to radically increase consumption of poor quality food by the poor. Obesity and diabetes rates are high and rising at rates which will soon generate health costs greater than smoking.

Physical exercise

Physical work is less necessary in the west, reducing appreciation of the value of recreational activity to maintain physical and mental health. The physical capacity of the average adult in affluent nations is declining, with the greatest decline among the poor as cheap commercial food provides an increasing share of unhealthy family meals.

Sporting organisations are growing more commercial, more competitive, less community based, encouraging an elite minority while discouraging the majority from participation in organised sport. Watching and talking sport is not healthy; aggression is not character, it is a building block for dominance and violence.

Chart 10: Percent of population overweight or obese, 1980 and 2013 Australia

“Class perspective” The personal is political:

The power of this affirmation, so evocative of American feminism, suggests this simple message resonates with many levels of human experience. The social constraints on domestic life—home, housework, family and children—is the first, obvious layer. Male advantage across productive and domestic work, so persistent it frequently compromises couples’ personal support and sexual exchanges, is another.

Another interpretation is important too, related to our struggle for clarity among the complexity of modern life. Our busy brains typically oversimplify and misrepresent based on our limited personal experience. We need diverse engagements to understand our world, but even diversity isn’t enough. To take class analysis beyond superficial simplifications requires more experience of working and sharing together, of debate in more equal forums, of community groups building alternatives denied in the mainstream. We need experiences which are both diverse and egalitarian, because without equity underlying those personal relationships, we are drawn to deceive ourselves and others, happily repeating explanations to justify self-interest.

Sharing domestic tasks to make both partners’ lives easier and happier, cooking for guests to create a small sharing community, seeking innovation by building relationships with people who expand and inspire our lives; these example of cooperation don’t change the world, but they are good training for the first step, understanding our world. All co-operative elements in our work, family and community lives have special value; they open up our potential to see our world as it really is, the very complex combination of billions of lives layered back through generations.

And seemingly small personal experiences sometimes shift our views through their parallels with larger social questions niggling away in our unconscious mind. Lately I’ve thought a lot about the west’s pressure on families through increased hours for both partners. Is falling family size a positive choice related to better birth control, or a reflexion of lost domestic happiness? When this debt-funded mirage lifts, might we make a shift to a more sustainable world, consuming less and working less, even engaging more to ensure a fairer world?

This revision of marxism, the very broad view of “class analysis” presented here, includes production, reproduction and all the rest of personal lives because there is no part of the social fabric which can be ignored if we seek knowledge to understand and influence our world.

Health and recovery

Medical advances have lengthened lives by fixing many illnesses and most injuries but a growing share of the population have become dependent on chemical solutions to social and behavioural problems. The continuing growth of male dominated medical interventions in women’s lives (hospital births and caesareans, cosmetic dentistry and surgery) reinforce commercial solutions ahead of personal health.

Recreation, relaxation, reflection

Passive commercialised “recreation” is displacing active organised participation in sport. Time to relax among friends and in nature, time to discuss and reflect has reduced. Personal entertainment is shifting away from people gathering together, towards people sharing virtual links about someone else’s life.

Virtual entertainment

Recreational use of virtual online products with no real life value has increased exponentially, dominating many people’s personal lives and allowing commercial priorities to intrude into personal time. These new tools are addictive and will increasingly filter and control life choices, squeezing out real communication and alternative perspectives.

Online packages will be crafted to dominate free time with a mix of instant entertainment gratification and subtle integration with consumer culture. Applications will be free or appealing, but only until we’re too addicted to leave. This is the standard corporate model of establishing market dominance followed by monopoly profits. America’s dominance of the entertainment industry and enthusiastic integration of male violence in online culture will have growing real-world consequences.

Retirement

The current generation of western retirees got the easiest deal ever—plentiful jobs, easy home purchase, rising asset prices, generous pensions. The older working generation still has lifetime work prospects sufficient to provide a good retirement. For today’s youth, access to and quality of entry jobs has fallen, home ownership is harder, and their parents’ wealth is spent on housing and health over longer retirements. The working and middle class of this new generation will be poorer in retirement than their parents.

Part 2 Intersections between family, capitalism and government

Our personal lives as adults are lived under a large shadow; they are the leftover hours after our most alert time is spent meeting employment obligations which are strongly reinforced by the workplace hierarchy. Though our home life is under our own control, the shadow of work makes it harder for us to come home and assert quite different, sharing and egalitarian ways—to be different people—at a time when we’re tired and in a place where we’re socially isolated. In the short term it is often easier for women to accommodate than oppose male partners’ expectations of power and advantage carried over from the workplace. Surveys show rates of relationship satisfaction are lowest in poorer households, where there is less surplus to share around at home.

Even in rich countries like Australia today, a majority of couples still have to balance trade-offs between men’s higher rewards at work and women’s greater unpaid work at home. And while the total hours worked by men and women are nearing equality here, the combination of longer worked hours for couples and reduced employment security has increased pressures on families, making them more likely to separate and less likely to have children. Both sexes have less time and energy to create a satisfying personal life and are living less diverse, less connected, less healthy lives.

Beyond the west, gender differences in workplace rewards and in family roles are much more obvious. Male near-monopolies dominate whole sectors of many developing countries—political parties, government agencies, the courts and armies, small and large businesses—holding back both women and national development. The burden of gender disadvantage is more extreme in the developing world, but the potential gains from change are also greatest for impoverished families there.

Home ownership is by far the largest form of capital for most workers but purchasing a family home has become much more difficult all around the world. Family working hours, job insecurity, labour migration, wage inequality, speculative investment and social debt have all increased. As a result real house prices are higher and housing price cycles are more extreme, raising the risk of catastrophic losses for recent purchasers. Free market policies have decreased the incentives to build new affordable housing and made the pursuit of stable family home life significantly harder.

Increased working hours for couples

Full time employed couples of working age work longer paid hours today compared to the 1960s. Most of the increased hours come from women, leading to a steady fall in women’s hours of domestic work. Increased work hours and pace leave partners with less time to be helpful and relationships less likely to last.

Childcare

Households relocate more often for employment today, breaking family connections and support. Commercial childcare is replacing the extended family, reducing the net return on second incomes. A growing number of entrepreneurial women are providing small-scale home-based childcare.

The rise of marginalised employment

As production moved out of the rich western countries, part time and insecure jobs replaced higher paid skilled work. Young people entering the workforce are much more likely to have insecure employment, limiting their progress to skills and higher rewards. Japan’s long recession and rigid corporate hierarchies show how much this can affect family life, with just 25% of irregular workers in their 30s married compared to 70% of men in their 30s with regular jobs (Katz/Financial Review “Broken Arrows”).

Labour mobility

Globalised corporations and European Union migrant labour have increased employment mobility, reducing neighbourhood and family connections. Individuals are more vulnerable to the latest spin, less connected to their cultural roots. Class perspectives like labour’s organisational lessons from the 1930s depression or the connection between the 1980s’ organised wage rounds and social equity are more easily forgotten.

Male dominated unions

Feminists promoted equal pay for work of equal value in the 1980s but traditional male dominated unions were more able to survive the free market onslaught which followed. Today, more professional, egalitarian and participatory unions are slowly re-emerging. Promoting equal pay is doubly important today because it would provide equity for women and better prospects for all workers stuck in insecure service jobs.

Employment inequality

In Australia today the gender pay gap across all industries averages 24.7%, with the largest sector gaps in the male dominated finance (37.8%) and legal sectors (35.6%, Workplace Gender Equality Agency, 2014). This gap results from a complex combination of direct wage discrimination, different career choices for men and women, differences in educational level, traditionally male jobs which pay men more for work of equal value and are less women-friendly, time off the career track when women have children and parents (usually women) opt for less-demanding jobs to have more time and energy at home.

China provides the most striking example of employment and gender inequality. Extremely rapid growth put a premium on skilled workers, increasing wages dramatically, but with more men employed in the better-paid and faster-growing manufacturing sector the income gap between China’s men and women has widened between 1990 to 2010. Compositional analysis confirms that the wage gap is reduced by economic development but increased by expansion of the market economy. China’s women have a comparitively high workforce participation rate; in most developing nations women still face a huge imbalance in power and access to employment.

Armies, paramilitaries, prison workers

Rich countries’ armed forces hierarchies increase the cultural incentives for violence and war while imposing high social costs for the benefit of under trained and under skilled men who do minimal productive work. In addition to ending and damaging the lives of low-ranked soldiers, today’s armies are not well prepared for interventions to reduce conflict or to respond to disasters, nor do they do a good job of preparing men for after-army working life and after-hours domestic life.

Investment skills

In a large study of investment data, men traded more often than women, single men traded less sensibly than married men, married men traded less sensibly than single women (Barber and Odean “Boys will be boys” MIT Quarterly Journal of Economics 2001). Data analysis consistently shows huge corporate bonuses cannot be justified by skills differences between the recipients.

Commercial food

Food production in the home has declined as family working hours increased and the cost of purchased meals fell, but the personal health costs as well as the social costs of western obesity are rising so fast they can no longer be ignored.

The standard business model for franchises is first to drive out competition with scale, visibility, quality and low pricing, then reduce quality and raise costs once the sector is controlled. Junk food followed this model and is now so pervasive it appears normal, with schools and sports club accepting sponsorship and promotion from corporations built upon undermining children’s health. Changing eating choices will be hard but not so long ago smoking appeared equally entrenched, and the social cost of obesity is rapidly overtaking the cost of smoking.

“Class perspective” Limiting free markets:

Junk food is an obvious example of the natural drive for profit-driven industries to expand the boundaries of free markets until the social costs (obesity in this case) reach unsustainable levels. The result is massive social transfers to global corporations from the poorest workers and consumers, and from government healthcare systems and reactive preventative programs.

In the current era of free market orthodoxy, we have failed to set meaningful limits on private markets and the consequences are obvious. To solve any problem of this scale the market intervention also has to be large scale, requiring evaluation of a complex set of trade-offs between market efficiency, social costs and intervention costs. A prerequisite before we can expect to see real solutions is a return to widespread public respect for a well-funded government as the most effective active agent to promote overall public-good solutions.

Health services

With longer lives, profit-driven hospitals and reduced primary care, health is now a larger share of household expenditure. Future affordability and quality will depend on the equity of taxation and the level of state support for public health services.

Education

Modern education is more gender neutral, increasing gender equality among children and young adults. Private education is increasingly subsidised by market-obsessed governments at the expense of public education and working class social mobility.

Communications media

Newspapers and television have been dumbed down to reduce costs, with analysis mostly replaced by crude American entertainment. Despite the media’s power the sector has below average profits; the real profit from media control is not on the balance sheets but in aligning the public policy agenda with corporate interests.

Housing

Housing capital plays a critical but under recognised role in today’s economies, even after America’s deceptive loan-based derivatives put housing on centre stage in the global financial crisis. Savings towards home purchase contribute the bank deposits which underpin home loans and business lending, and buying a home is most families’ only form of capital, their best chance for secure retirement. If we learn only the simplest lesson from 1980 to 2020, future housing incentives must change to discourage speculative unaffordable housing and incentivise affordable housing.

“Class perspective” Affordable housing can assist both families and capital:

Housing tenure varies widely across the western world. Private rental comprises 60% of housing stock in Germany today compared to 67% home ownership in Australia; social renting provides 19% of housing in the Netherlands, 4% in Australia and 0% in Germany (Haffner/AHURI 2012). Provided there are mechanisms to ensure affordability and security of tenure, many solutions can provide satisfactory short term housing.

Over the longer term though, Australian research confirms the intuitive conclusion that low to moderate income households are better off after a few early years of financial austerity if they purchase rather than rent their home (Hulse Burke Ralston Stone/AHURI 2010).

Home ownership rates are high in Australia because incomes are high, but recent housing policy has encouraged speculative capital to dominate in both housing supply and rental markets. Land release legislation is complex so land developers are large, while most housing construction companies are small. This imbalance allows land developers to bank land and maximise their return at sale, pushing builders towards higher-cost, higher-return housing. Tax policy favours landlords through negative tax gearing and reduced capital gains taxes, which supports rental property purchases with minimal capital.

As a result of these policies and easy credit, house price increases since the 1990s have far outpaced real income growth and house construction is biased to expensive homes, leaving a shortage of affordable rental. This is an unstable equilibrium, where the high burden on new home purchasers is balanced against their precarious dream of capital gains.

The benefits flow to older established home-owners, particularly investors; the costs and risks are passed to younger renting and purchasing households. If changed government policies made home purchase for residence more affordable, real living standards for working households would rise and reduce the pressure for wage increases.

Working households must also save for retirement, and superannuation and home ownership compete as the two most efficient means to smooth living standards over the whole lifecycle. In this rising housing market driven by speculative investment, home ownership has attracted an artificially high share of household debt and savings. Bank lending for housing in Australia has grown from 24% in 1990 to 60% 2013 (Reserve Bank of Australia, Bank lending by category).

Freeing more savings for superannuation would also benefit the whole economy, because today’s giant superannuation funds target long run stable profits through investment in the productive economy and national infrastructure.

And if government’s tax and regulatory incentives were crafted to be anti-cyclical by encouraging affordable housing construction and employment in lean times but discouraging purchase of investment properties in booms, general demand would be boosted when needed but restrained in good times to discourage boom-and-bust cycles.

Population growth

Nearly half the world’s population lives in nations where fertility rates are below replacement levels but the global annual growth rate is still 1.14% (United Nations), driven by increased life expectancy as health care improves. Global population pressures raise the cost of limited natural resources, increasing economic instability.

Ageing populations

Longer lives have added to the social costs imposed on the productive sector. Post-war Japan was the first country to hit the resulting demographic bulge, with government stimulus creating a housing bubble and the ‘lost decades’ of zero growth. China is just starting that transition, and the west is not far behind.

Economic crises

Family expenditure declines if unemployment rises, becoming much less responsive to state stimulus as long as employment prospects remain uncertain. In rich countries today, a large share of purchases are non-essential and spending is increasingly funded by rising debt. Households are making rational decisions to lower their long term spending, living longer with parents or in share houses, adopting alternative lifestyles—while business and government continue to chase unrealistic growth.

Cultural traditions

Every nation and community is influenced by past practices and cultures, some supporting gender equity and some undermining it, while today’s institutions constantly reshape those traditions. Government and community groups play a critical role in mediating these transitions, for better or for worse.

Feminist organisation

Discussion of gender inequality is no longer part of mainstream public debate. Participation in feminist organisations with an explicit commitment to gender equality has declined as gendered privilege increased for the west’s most wealthy families, leaving working women less organised to fight for change. Class analysis emphasises the importance of social organisation to both knowledge and action. Separate organisational forms for women, particularly working women, are a necessary part of increasing gender equality, and gay and lesbian organisations form a natural part of the movement for gender equity.

Annie Lennox:

Why are we not valuing the word ‘feminism’ when there is so much work to be done in terms of empowerment and emancipation of women everywhere?

Family: Future prospects

Every nation is different and all are complex, needing their own analysis. For women in Iraq or Sudan, the major concern may shift to male dominance of military aggression, religion, government, courts and families. In China, the priority might be creating a social safety net or building affordable rental housing to replace factory dormitories and luxury apartments. International differences in patriarchy can be extreme, but in every nation more equal economic rewards and political participation would create a better world for women and men.

The disadvantage of women in poorer developing nations is striking, despite research evidence for their greater capacity to sustain small businesses. Lower female work participation rates and male dominance in families, businesses and government brings with it men’s control of economic assets and family finances, as well as their weakness for putting personal privileges and short term payoffs ahead of long term stability.

One gender difference found consistently in research is the gap in life expectancy between men and women across all nations and levels of development. Research attributes the majority of men’s shorter life expectancy to tobacco and alcohol use; that preference for short term rewards reinforced by traditional male cultures and most prevalent in countries like Japan and Turkey. This international life expectancy gap is a reminder that despite all the diversity and complexity across national gendered cultures, the average experience across all men’s lives remains significantly different to women’s. The net economic and power advantages of men is measurable and demonstrable—but that class difference comes at a cost even to men.

At the national level, pro-rich government housing policies in both rich and poor nations are a key contributor to family pressures. From China’s pricy apartments while workers live in factory dormitories, to the west’s runaway property markets driven by investor tax breaks and quantitative easing, planning for affordable housing is all words and no capital investment. The interrelationships between male economic and domestic domination and male political cultures is a pervasive force supporting social inequity in all these forms.

Family life is in steady retreat today under the pressure of business practices and housing markets which have changed too much and patriarchal politics which haven’t changed enough—increasing work hours and intensity, decreasing job security, labour migration, commercialised recreation, housing speculation, institutional male bias. Families, just like global production, could become either more or less sustainable in our future world, depending on the path we take from here.

If class analysis is to move away from its roots as a chauvinistic movement pushing for revolutionary conflict, we have to start by acknowledging the scale of male social dominance today and the absence of effective counter-movements.

Family: Equity priorities

- Promoting evidence based development models in developing nations, including more support for women.

- Anti-cyclical policies after the housing bubble bursts to keep housing affordable.

- Campaigns for equal pay for work of equal value and against discrimination

- Increasing working class feminist influence in community, workplace and political organisations.

- Opposition to war and demilitarisation of society, reducing physical violence and all forms of social coercion.

- Supporting diverse and equitable relationships as alternative role models to those promoted by competitive capitalism and manipulative political parties.