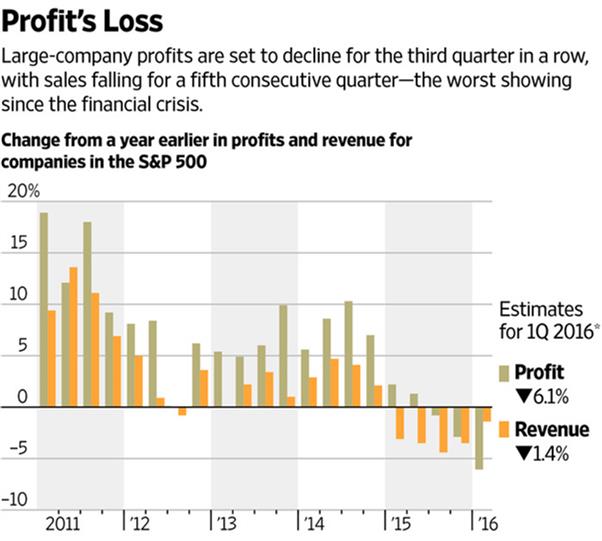

Large-company profits falling

As profits fall, investors are pulling back from over-leveraged corporations. In the last year, earnings growth has petered out and, in many cases, turned negative. This has made the sharp increases in corporate debt in the post-crisis era look far harder to sustain.

Perhaps the most alarming illustration of the problem compares annual changes in net debt with the annual change in earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation, which is a decent approximation for the operating cash flow from which they can expect to repay that debt. Debt has grown at almost 30 per cent over the past year; the cash flow to pay it has fallen slightly.

According to Andrew Lapthorne of Société Générale, the reality is that “US corporates appear to be spending way too much (over 35 per cent more than their gross operating cash flow, the biggest deficit in over 20 years of data) and are using debt issuance to make up the difference”.

A further issue is the uses to which the debt has been put. As pointed out many times in the post-crisis years, it has generally not gone into capital expenditures, which might arguably be expected to boost the economy. It has instead been deployed to pay dividends, or to buy back stock — or to buy other companies.

Cash-funded mergers and acquisitions are at a record. In the four quarters to the end of last September, according to Ned Davis Research, S&P 500 companies spent $376bn on acquisitions, 43 per cent above the prior high in 2007, just ahead of the last credit crisis.

However, this year, repurchases have fallen sharply. Companies tend to cut down on buybacks and instead conserve cash when they are worried about growth.

Meanwhile, dividend payouts continue to grow, with an increase of 4.6 per cent in the first quarter of this year compared with the first quarter of last year across all US stocks, according to S&P Dow Jones.

How is the use of cash affecting markets? The clearest symptom that leverage is now a source of concern comes from the market’s attitude to share buybacks. It is not just that companies are buying back less of their own stock. It is also that investors are far less enthused to buy the companies that do so because they are becoming concerned about the impact on company prospects.

Meanwhile the ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats ETF, which tracks companies that pay a high dividend yield, has gained 4.9 per cent. Such popularity for companies that pay out dividends is generally a sign of bearishness and lack of trust. If investors want to be shown the money in this way, it suggests very low confidence in companies’ ability to use the cash wisely.

Companies can of course afford to stay highly levered without too much difficulty, while they enjoy fixed low rates. The problem, and the reason that investors have now started to focus on the problem, is producing the earnings and cash flows needed to pay their debt. That is why earnings are being watched with such anxiety.

Source: Alarm over corporate debt and stalled earnings, John Authers FT 27 April 2016 www.ft.com