Beyond the Panama Papers

So far, this is the world’s largest data leak. I can’t wait for more leaks to fuel the fight-back against tax evasion.

This massive security breach showed how a global industry of law firms and big banks sells financial secrecy to politicians, fraudsters, drug traffickers and billionaires. The cache of documents includes emails, banking details and client records dating back 40 years and reveals the inner workings of a law firm famed for its secrecy.

Using complex shell company structures and trust accounts Mossack Fonseca services allow its clients to operate behind an often impenetrable wall of secrecy.

Mossack Fonseca’s success relies on a global network of accountants and prestigious banks that hire the law firm to manage the finances of their wealthy clients. Banks are the big drivers behind the creation of hard-to-trace companies in tax havens. Commerzbank, HSBC and Societe Generale are all clients.

How much more is there?

Mossack Fonseca is being referred to as “the world’s fourth biggest offshore law firm” but it doesn’t even rate a mention in Wikipedia’s list of the “offshore magic circle”. They’re not telling, but imagine how many more scandals are yet to be uncovered from all the rest…

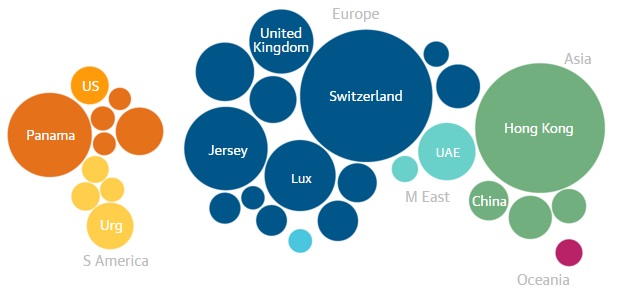

Where are the hiding places:

Where are the intermediaries?

Suggested responses in Bloomberg article

“Rather than blame the banks for such transactions, international attention should focus on requiring disclosure of the end of the chain owners of shell companies, eliminating the ability of the unscrupulous to misuse the banking system and create vast compliance costs for legitimate businesses,” Peter Hahn, a professor at London’s Institute of Financial Services, said in response to e-mailed questions.

Williams of Boston University was blunter. “The money-washing business is global in scope and will not be eliminated until banks, law firms and other enablers are held accountable and pay for facilitating such illegal actions,” he said. “Fines may not be enough. It might also be necessary to have the power to close down such businesses, creating the ultimate disincentive for such bad actors to break the law.”

ICIJ interactive summary of key public figures caught out: ICIJ presents Whos Who

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists home page

For more information on fighting tax avoidance:

Tax Justice Network site: taxjustice.net

Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index for nations: financialsecrecyindex.com

Tax Justice Network estimate of hidden wealth $21-32T (2012): taxjustice.net

Global Financial Integrity site: www.gfintegrity.org/

Five in-depth articles follow:

1. How reporters pulled off the biggest leak in whistleblower history

More than a hundred media outlets around the world, coordinated by the Washington DC-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, released stories on the Panama Papers, a gargantuan collection of leaked documents exposing a widespread system of global tax evasion.

The leak includes more than 4.8 million emails, 3 million database files, and 2.1 million PDFs from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca that, according to analysis of the leaked documents, appears to specialize in creating shell companies that its clients have used to hide their assets.

“This is pretty much every document from this firm over a 40-year period,” ICIJ director Gerard Ryle told WIRED in a phone call, arguing that at “about 2,000 times larger than the WikiLeaks state department cables,” it’s indeed the biggest leak in history.

The leak represents an unprecedented story in itself: How an anonymous whistleblower was able to spirit out and surreptitiously send journalists a gargantuan collection of files, which were then analyzed by more than 400 reporters in secret over more than a year before a coordinated effort to go public.

The Panama Papers leak began, according to ICIJ director Ryle, in late 2014, when an unknown source reached out to the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung, which had reported previously on a smaller leak of Mossack Fonseca files to German government regulators.

A Suddeutsche Zeitung reporter named Bastian Obermayer says that the source contacted him via encrypted chat, offering some sort of data intended “to make these crimes public.” But the source warned that his or her “life is in danger,” was only willing to communicate via encrypted channels, and refused to meet in person.

After seeing a portion of the documents, Suddeutsche Zeitung contacted the ICIJ, which had helped to coordinate previous tax haven megaleaks including a 2013 analysis of leaked offshore tax haven data and another leak-enabled investigation last year that focused on assets protected by the Swiss bank HSBC. ICIJ staff flew to Munich to coordinate with Suddeutsche Zeitung reporters.

The ICIJ’s developers then built a two-factor-authentication-protected search engine for the leaked documents, the URL for which they shared via encrypted email with scores of news outlets including the BBC, The Guardian, Fusion, and dozens of foreign-language media outlets.

The site even featured a real-time chat system, so that reporters could exchange tips and find translation for documents in languages they couldn’t read. “If you wanted to look into the Brazilian documents, you could find a Brazilian reporter,” says Ryle. “You could see who was awake and working and communicate openly. We encouraged everyone to tell everyone what they were doing.” The different media outlets eventually held their own in-person meetings, too, in Washington, Munich, London, Johannesburg and Lillehammer, Ryle says.

Ryle says that the media organizations have no plans to release the full dataset, WikiLeaks-style, which he argues would expose the sensitive information of innocent private individuals along with the public figures on which the group’s reporting has focused. “We’re not WikiLeaks. We’re trying to show that journalism can be done responsibly,” Ryle says. He says he advised the reporters from all the participating media outlets to “go crazy, but tell us what’s in the public interest for your country.”

Weeks before contacting the subjects of the investigation, including Mossack Fonseca, Obermayer took one final precaution: he destroyed the phone and the hard drive of the laptop he’d used for his conversations with the source. “This may have seemed a little overachieving,” he notes, “But better safe than sorry.”

He notes that even now, he doesn’t know who the source actually is. “I don’t know the name of the person or the identity of the person,” Obermayer says. “But I would say I know the person. For certain periods I talked to [this person] more than to my wife.”

Mossack Fonseca and its customers won’t be the last to face an embarrassing or even incriminating megaleak. Encryption and anonymity tools like Tor have only become more widespread and easy to use, making it safer in some ways than ever before for sources to reach out to journalists across the globe. Data is more easily transferred—and with tools like Onionshare, more easily securely transferred—than ever before. And actual Moore’s Law continues to fit more data on smaller and smaller slices of hardware every year, any of which could be ferreted out of a corporation or government agency by a motivated insider and put in an envelope to a trusted journalist.

The new era of megaleaks is already underway: The Panama Papers represent the fourth tax haven leak coordinated by the ICIJ since just 2013. The Intercept, the investigative journalism outlet co-founded by Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras and Jeremy Scahill, has also shown how encryption tools can be combined with investigative journalism to yield leaks like last year’s Drone Papers and a collection of 70 million prison phone call records. Dozens of media outlets, including the Intercept, now host anonymous upload systems that use cryptographic protections to shield whistleblowers. All of that—unfortunately for companies and governments trying to keep hold of their dirty data, but fortunate for public interest—means that the widening pipeline of leaks isn’t likely to dry up any time soon.

Edited from Wired.com http://www.wired.com/2016/04/reporters-pulled-off-panama-papers-biggest-leak-whistleblower-history/

2. Why tax evasion is so hard to pin down

In the coming days you will hear a lot about the difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion.

‘Avoidance’ is – whatever your views of its moral quality – lawful. ‘Evasion’ usually involves deception and is unlawful. You go, theoretically at least, to prison for offshore tax evasion. (‘Theoretically’ because HMRC tend not to bring prosecutions for this type of behaviour. As of November 2015 there had been only 11 prosecutions for offshore tax evasion in the last five years.)

Professional firms and others whose business it is to service or speak for those amongst the wealthy who prefer not to pay their taxes will be out in force in the newspapers and the media channels. Having assets in, or which have passed through, Panama is consistent with avoidance, they will tell you.They – and, too, the Government which will want to defend its record in this field – will suggest that the outrage you feel about what you read you are wrong to feel. And that people can perfectly lawfully have assets in Panama. And that you cannot conclude from the fact that name X or name Y has appeared in the Panama Papers that X or Y has done anything wrong.

And you won’t be able to contradict them. You won’t know whether Mr X or Mrs Y have declared their tax liabilities on those assets in the UK. You have no entitlement to know anything about their UK tax affairs.

HMRC won’t tell you. HMRC is bound by a duty of confidentiality – and that duty is so very strict that if I was Mr X I could stand, smiling, on national news, next to HMRC’s Chief Executive and declare that I had paid every penny I owed and even if HMRC’s Chief Executive knew this an outrageous lie she would still not be able to contradict me.

Journalists won’t be able to tell you either. It is hard to have enough information to exclude every legitimate explanation for a fact pattern such that you can positively assert that Mrs Y is a tax evader. You will have had to tell Mrs Y in advance of what you planned to broadcast and Mrs Y’s lawyers will have issued very serious threats about what will happen if you broadcast – sometimes coupled with an almost comedically implausible explanation for the conduct. But the threats are serious and so you will not broadcast.

You may wonder who this wall of secrecy exists to protect. You may wonder whether the explanations of why it exists fairly balance public and private interests.

You will see something that feels very wrong. Yet no one will call it so. And because no one will call it wrong, no one will promise meaningful change. And this will make you angry.

It is true that tax avoidance is – whatever you think of its moral quality – legal. And it is true that people living in the UK might have assets in or that have passed through Panama for perfectly proper reasons. True, but not very likely. And here’s why.

For the purposes of UK tax law, most tax havens are the same. There is no magic effective in UK tax terms that can only be performed in Panama. Moreover, Panama is not next door. It is not a British tax haven with the comforting familiarity such brings. It does not enjoy an especial reputation for trust and solidity.

People think of these things when they are choosing where to put their money. They are big disadvantages for Panama. So there has to be a reason why you go there.

What Panama has offered – its USPs in the competitive world of tax havenry – is an especially strict form of secrecy, a type of opacity of ownership, and (if the reports of backdating are correct) a class of wealth management professionals some of whom have especially compromised ethics.

You go to Panama, in short, because, despite its profound disadvantages, you value these things.

And the question you should be asking is, what is it about this Mr X or that Mrs Y and his or her financial affairs that causes them to prioritise secrecy or opacity or (if the reports are correct) ethically compromised professionals above all else?

Perhaps it is not because the behaviour is criminal: tax evasion or money laundering or public corruption. Perhaps it is not. But – and especially in the case of Panama – very possibly it is.

Source: http://waitingfortax.com/2016/04/04/some-thoughts-on-the-panama-papers/

3. What’s so special about Panama?

What is important about Panama’s financial services industry? If you tap “Panama offshore” into Google you get a long list of adverts offering to set up a Panama offshore (secret) bank account for you.

For those wanting to establish a really secret tax avoidance scheme it is not good enough just to pick one offshore tax haven – say the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands. You need a series of interlocking offshore accounts in different jurisdictions to guarantee anonymity. British Virgin Islands is good for setting up companies and the Caymans provides extremely discreet bank accounts. Meanwhile Panama is tax exempt and stonewalls requests for company information from investigators in the rest of the world.

Offshore companies incorporated in Panama – and the owners of the companies – are exempt from any corporate taxes, withholding taxes, income tax, capital gains tax, local taxes, and estate or inheritance taxes, including gift taxes.

Panama has more than 350,000 secretive International Business Companies (IBCs) registered: the third largest number in the world after Hong Kong and the British Virgin Islands. Alongside incorporation of IBCs, Panamanian financial services are proactive in forming tax-avoiding foundations and trusts, insurance, and boat and shipping registration. Violation of financial secrecy is punishable by prison.

Panama ranks at 14th position on the 2015 Financial Secrecy Index. But it remains a jurisdiction of particular concern. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Pascal Saint Amans summed up the problem recently: “From the standpoint of reputation, Panama is still the only place where people still believe they can hide their money.”

The Tax Justice Network says that “until now Panama has been fairly indifferent to reputational issues, but the increased attention that Panama receives will inevitably raise concerns among the punters that Panama is no longer able to effectively protect the identity of the crooks and scammers attracted by its dodgy laws and equally dodgy law firms”.

TJN says Panama has long been the recipient of drugs money from Latin America, plus ample other sources of dirty money from the US and elsewhere – it is one of the oldest and best known tax havens in the Americas. In recent years it has adopted a hard-line position as a jurisdiction that refuses to cooperate with international transparency initiatives.

Edited from source: http://theconversation.com/panama-papers-remarkable-global-media-operation-holds-rich-and-powerful-to-account-57196

4. Not news in China

The Panama Papers are making headlines from Reykjavik to Sydney, but one place where there’s been conspicuous silence over the leak is China.

Documents from Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm that specializes in creating shell companies, reveal offshore companies linked to Deng Jiagui, who is married to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s older sister, as well as Li Xiaolin, the daughter of Li Peng, the former premier.

Details of the documents—though not the papers themselves—were published Sunday in Süddeutsche Zeitung, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, and other news outlets worldwide.

At least one Chinese provincial office has issued a censorship directive to editors on the story. “Find and delete reprinted reports on the Panama Papers. Do not follow up on related content, no exceptions,” said the directive from the unnamed province, which was obtained by the China Digital Times, a China-focused website that is based in Berkeley, California.

“If material from foreign media attacking China is found on any website, it will be dealt with severely. This directive was delivered orally to on-duty editors. Please act immediately.”

A similar directive was issued to editors on stories related to the leak that allege close associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Bank Rossiya, a Russian bank that has been blacklisted by the U.S. and the EU, laundered hundreds of millions of dollars.

The directives appear to have had the desired effect. Stories related to the Panama Papers in the Shanghai Daily as well as CCTV, the state-run broadcaster, were purged. Neither of those stories mentioned the China-related allegations.

The Chinese allegations contained in the papers themselves aren’t new. In 2012, Bloomberg reported on Xi, who at the time was tipped to become the new Chinese leader. The news report said that as Xi climbed the ranks of the Communist Party, his extended family expanded their business interests and grew increasingly wealthy, but none of their assets were traced to Xi or his wife.

“Most of the extended Xi family’s assets traced by Bloomberg were owned by Xi’s older sister, Qi Qiaoqiao, 63; her husband Deng Jiagui, 61; and Qi’s daughter Zhang Yannan, 33,” the news agency added. Qi and Deng are the figures also named in ICIJ’s Mossack Fonseca documents.

Similar stories about the wealth of Chinese officials were published that year by The New York Times and in 2014 by the ICIJ, in its previous reporting on leaked documents. Although those stories have made it widely known that influential Chinese have offshore assets, along with great wealth, there’s no reporting on it in China’s state-run media—though it does occasionally creep into the country’s vibrant social media before being censored. Some of that censorship was on display after Sunday’s stories. “Panama” was a highly censored term on social media, according to Free Weibo, a website that tracks censorship.

The one mention of the Panama Papers, but not the allegations against the Chinese figures, came in an editorial in The Global Times, a tabloid published by the People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece. The editorial, titled “Powerful force is behind Panama Papers,” suggested that only non-Western figures were being targeted.

When asked Tuesday about the accusations detailed in the Panama Papers, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman would only say: “For these groundless accusations, I have no comment.” But even those remarks were omitted from the Foreign Ministry’s official transcript of the event.

Source: http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/04/panama-papers-china/476889/

5. The US connection

Years before more than a hundred media outlets around the world released stories Sunday exposing a massive network of global tax evasion detailed in the so-called Panama Papers, U.S. President Barack Obama and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton pushed for a Bush administration-negotiated free trade agreement that watchdogs warned would only make the situation worse.

Soon after taking office in 2009, Obama and his secretary of state — who is currently the Democratic presidential front-runner — began pushing for the passage of stalled free trade agreements (FTAs) with Panama, Colombia and South Korea that opponents said would make it more difficult to crack down on Panama’s very low income tax rate, banking secrecy laws and history of noncooperation with foreign partners.

Even while Obama championed his commitment to raise taxes on the wealthy, he pursued and eventually signed the Panama agreement in 2011. Upon Congress ratifying the pact, Clinton issued a statement lauding the agreement, saying it and other deals with Colombia and South Korea “will make it easier for American companies to sell their products.” She added: “The Obama administration is constantly working to deepen our economic engagement throughout the world, and these agreements are an example of that commitment.”

Critics, however, said the pact would make it easier for rich Americans and corporations to set up offshore corporations and bank accounts and avoid paying many taxes altogether.

“A tax haven … has one of three characteristics: It has no income tax or a very low-rate income tax; it has bank secrecy laws; and it has a history of noncooperation with other countries on exchanging information about tax matters,” Rebecca Wilkins, a senior counsel with Citizens for Tax Justice, a nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates changes in U.S. tax policy, told the Huffington Post in 2011. “Panama has all three of those. … They’re probably the worst.”

The Panama FTA pushed for by Obama and Clinton, watchdog groups said, effectively barred the United States from cracking down on questionable activities. Instead of requiring concessions of the Panamanian government on banking rules and regulations, combating tax haven abuse in Panama could violate the agreement. Should the U.S. embark on such an endeavor, it could be exposed to fines from international authorities.

“The FTA would undermine existing U.S. policy tools against tax haven activity,” warned consumer watchdog group Public Citizen at the time, saying the agreement would encourage corporations to thwart any U.S. efforts to combat financial secrecy. The group also noted that U.S. government contractors, as well as major financial firms supported by taxpayer bailouts, stood to gain from the trade deal’s provisions that could make it harder to crack down on financial secrecy.

Despite the warnings from watchdog groups, some Democratic lawmakers urged the Obama administration to aggressively push for the Panama agreement. According to a 2009 email sent to Clinton by her top State Department aide, high-ranking then-Sen. Max Baucus, D-Mont., was pushing for passage of the Panama and Colombia free trade pacts, and Rep. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., said “the president had to lend his star power to pushing them through.” Obama ultimately did just that, hosting Panama’s president at a 2011 Oval Office event touting the proposed trade pact.

Major corporations also lobbied for the deal, including, among others, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, which at the time maintained 136 Panamanian subsidiaries, according to the Huffington Post.

Before the agreement was ratified, the Obama administration did forge a tax information sharing agreement with the Panamanian government that it said would increase financial transparency. Public Citizen, however, asserted that the separate agreement “does not remedy these problems” of secrecy, noting that it “merely requires Panama to stop refusing to provide information to U.S. officials on specific cases if U.S. officials know to inquire.”

The Sunday reports on the so-called Panama Papers exposed nearly 40 years’ worth of information that included more than 11 million documents on more than 210,000 companies, trusts, foundations and world leaders with offshore dealings in Panama where money laundering, tax avoidance and crime (including funding terrorism) are made easy. The leak, from financial services firm Mossack Fonseca, shows that the organization helped clients perform all of those acts.

The leaks have revealed a suspected billion-dollar money laundering ring that includes many close allies and associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin, and showed that Icelandic Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugson has been hiding interest linked to his wife’s wealth. A total of 12 current or former heads of state and 60 people linked to current or former leaders have been revealed to have had secretive dealings in Panama.

Edited from source Clark Mintock: http://www.ibtimes.com/panama-papers-obama-clinton-pushed-trade-deal-amid-warnings-it-would-make-money-2348076