Fixing the Euro

The Euro was supposed to encourage convergence between participating nations through shifting capital investment from the center to the periphery. Capital moved, but only to create unsustainable property booms, so the gap widened instead. This article explains why the Euro failed and how it could change. Short summary below, full article here

Nations gave up trade and industrial policies which protected local industries to join the Union. To join the common currency, they gave up two other essential economic policy levers – monetary policy and fiscal policy, which provide responses in crises.

The Euro area was too diverse for a currency union. Countries with very different economies will experience crises at different times, and now the only national responses left was to emigrate to find a new job.

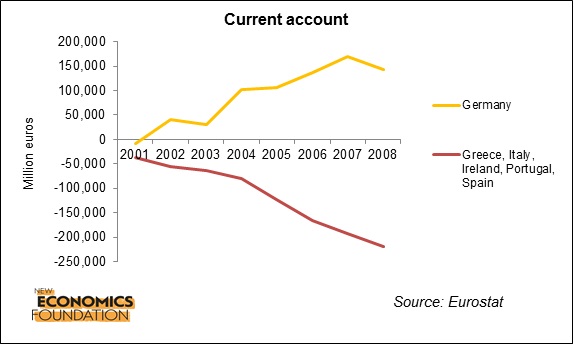

Additionally the increased capital flow to peripheral countries caused inflation, which undermined export competitiveness. And the centrally set Euro currency was too strong relative to these weaker economies. Finally, Germany as the richest member chose to lower wages from the late 1990s, which increased their exports while decreasing their imports of products from the periphery.

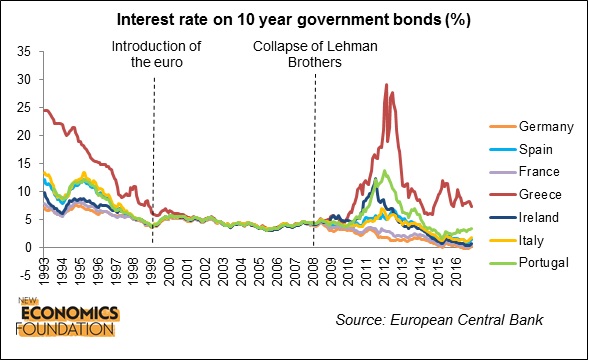

The resulting combination of trade imbalances temporarily balanced by speculative financial flows, led to a radical reset of interest charged on sovereign debt after the 2008 financial crisis. With no other tools to respond, the Eurozone imposed austerity and asset sales on poorer members, which further increased the gap between rich and poor member nations.

The paper proposes major reforms, including a central mechanism to issue sovereign debt at reasonable rates, a clean-up of European bank debts, a coordinated effort to increase demand across the EU, while longer term adding federal funding for common unemployment support.

For this to happen the EU also needs far more democratic central institutions, so citizens have confidence in the programs they are funding.