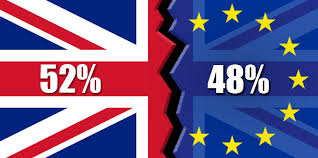

Review: “Brexit: How Britain left Europe”

Britain’s exit highlights a lot of the really big questions which are unanswered by modern politicians and economists. Are referendums more or less democratic? Do free trade and free financial markets really have net benefits for nations and populations in the long run? Would reinstating national tarrifs and reducing internal labour migrantion create healthier working lives and communities? Is the EU essential to ensure future stability and peace in europe? How could the EU be modified to make it more democratic, participative and popular in Europe?

Britain’s story to date is medium-term, so there are no definitive answers in Macshane’s book, but as one of the most active and objective participants in the debate, he fills in a lot of information about the British experience, and highlights the vested interests which promoted this referendum and the exit vote.

This is a book that speaks for itself – very well written and based on first hand experience – so here some key quotes from Macshane:

“Rich right-wing businessmen had amasssed fortunes in the Thatcher era”

“Fifty-two per cent of (post-Thatcher) British households are net recipients of state handouts – pensions, child benefits, disability allowances, working tax credits, social service care and so on”

“British productivity is thirty percent lower than France”

“The key to (US based UK media owner) Murdoch’s line on Europe is not hostility to the EU so much as blind pro-Americanism. One of the consistent themes in the political line which he encouraged on the Times was that he saw the EU as a rival to the US. He bitterly opposed those Conservatives who wanted Britain to have a degree of independence and some critical distance from the US” (Macshane quoting Murdoch biographer David McKnight)

“the anti-European campaigns had not only the resources of the EU-hostile press that daily printed propaganda against Europe, but also some of the richest businessmen in Britain and the speculators of the hedge funds, derivative trading and spread-betting industries who saw Europe as a threat to their view of how a market economy should be organised”

“of great concern to the City’s financial services sector, too many proposals that appeared to hinder rather than help the City in its new role as a global financial hub no longer moored in a national, let alone a European framework of rules and obligations”

“(London) lectured the rest of the EU on why the euro was a bad project and why a return to francs and D-marks to rejoin the pound in a paradise for money traders and speculators was better for Europe”

“When the then Polish foreign minister, the Oxford-educated Radek Sikorski, and the then German foreign minister, Guido Westerwelle, published their joint article under the headline ‘New Vision of Europe’ in September 2012, the New York Times gave them star billing on the paper’s comment pages. The idea of a British foreign secretary writing in visionary terms about Europe is unthinkable. In Britain, politicians do not do vision”

“the classic social democratic reformism of northern Europe had little purchase on the British left”

“Referenda are the nuclear weapons of democracy. In parliamentary systems they are redundant. Seeking a simplistic binary yes/no answer to complex questions, they succumb to emotion and run amok. Their destructive aftermath lasts for generations” (Macshane quoting Jeremy Kinsman, former Canadian High Commissioner in London)

And one more key story. After Thatcher’s war on unions, Macshane recalls the rapturous response at the 1988 congress of trade unions when European Commission President Jacques Delors advocated a Europe with guaranteed worker rights, education and participation in companies. This was the point where the conservative party realised europe was a social package, not just free markets and trade, and they did not like it.

Summing up, Macshane descibes British politicians as inward looking and unrealistic, industry and agriculture as less efficient, the financial sector as self-serving and anti-regulation, the mass media as unnaccountable liars. For him, Brexit was no surprise.

This very British Brexit debate also highlights many questions New Zealanders need to ask, and answer. Europeans’ wish to prevent future wars was the single biggest underlying motivation for starting the EU project. How can all nations best provide for defense and security in the modern world, while avoiding the destructive consequences of the armanments trade and wars?

Do regional free trade and financial agreements really benefit citizens? Do we really want to follow this European path where millions leave home to become migrant workers in Germany?

And if you answered no, what are our alternatives? Could the EU introduce a system which allows national variants of the Euro as suggested by Stiglitz? Should nations retain some level of tariff within regional markets to protect local production? How can we ensure trans-national companies pay national taxes which match their earnings? How to reduce abuse of market monolies? Should we mandate worker participation on boards to reign in executive excess? What about a right to work not just income?

Beyond economics, all nations can learn a lot from following the debate about Europe’s future, the strengths and weaknesses of current European political structures, and particularly the broader European debate about what “Social Europe” should look like in the future (see www.socialeurope.eu).

Reading about the differences between European and British views of the EU highlighted for me that despite all the lofty intentions in Europe, and even with all the regulation of the EU, the single free market remains a very American concept. “Free” movement of labour looks pretty forced in reality, when youth unemployment in France and Spain is still over 30%.

The other side of that is lost capital. Human capital in lost skills. National capital in old ways of production completely wiped out. Do we really want to become nations of specialists? What exactly will be left for those nations with few national resource advantages?

“Brexit: How Britain left Europe” by Denis Macshane (2015, revised 2016) I.B.Taurus